Overview

Description

Gastown was recognized as a Historic Area in 1971 by the Province of BC and the City of Vancouver, and as a National Historic Site by the Government of Canada in 2009. The neighbourhood provides a significant representation of the architectural, economic, and social history of the early years of Vancouver, with a cohesive collection of pre-World War I buildings and a street pattern inherited from the early colonial settlement.

History

Burrard Inlet has been occupied by humans for 4000 years. The south shore of the Inlet has long been important to First Nations peoples, principally the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Tsleil-Waututh, and Sḵwx̱wú7mesh. Sḵwx̱wú7mesh landmarks in the area of present day Gastown, include Lek’leki at the foot of Abbott and Carrall Streets where CRAB park is now, and Ḵ’emḵ’emel̓áy̓ further east, which the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm similarly call qəmqəmələɬp. The landscape was, before the 1860s, heavily forested in enormous cedars, the bark of which was harvested systematically, processed, and woven into articles of clothing and a variety of other products. What is now Carrall Street flooded at high tide, creating a water corridor from the inlet to False Creek

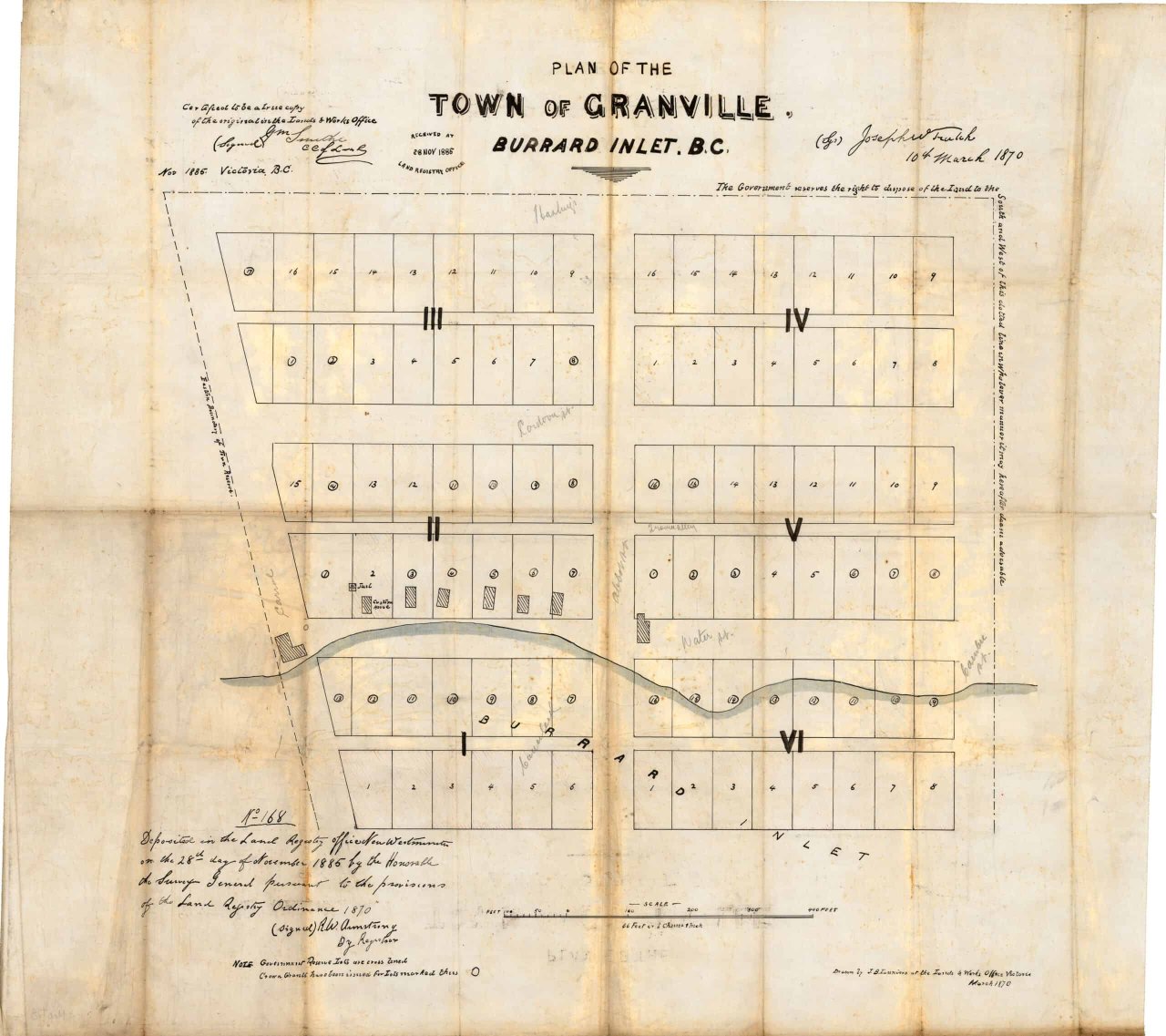

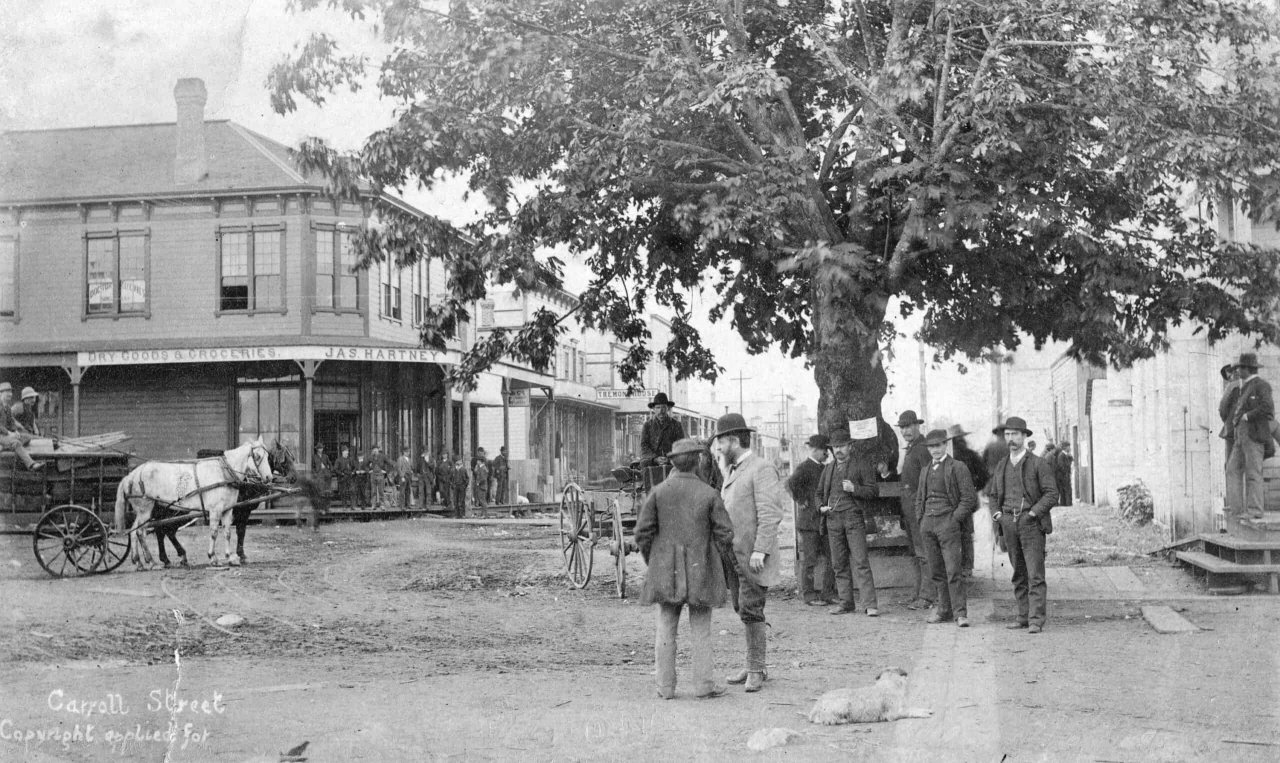

The non-Indigenous settlement of what is now called Vancouver begins with the establishment of Hastings Mill in 1865 at the foot of Dunlevy Street. A few years later, in 1867, the first saloon in the area was established about one kilometre to the west of the mill. This was opened by Captain John “Gassy Jack” Deighton, a saloon-owner who moved to Burrard Inlet from New Westminster. Three years later, the area was registered as the Granville Townsite, bounded by the water on the north, Cambie Street in the west, Hastings Street to the south, and Carrall Street to the east. Deighton’s Globe Saloon was built – by thirsty millworkers, according to local tradition – at Carrall Street and Water Street, on the edge of the stream that bisected the peninsula. Deighton’s role as the folkloric namesake of Gastown is controversial, however, with recent attention given to his second marriage to his first wife’s niece, Quahail-ya, a 12-year-old Squamish girl.

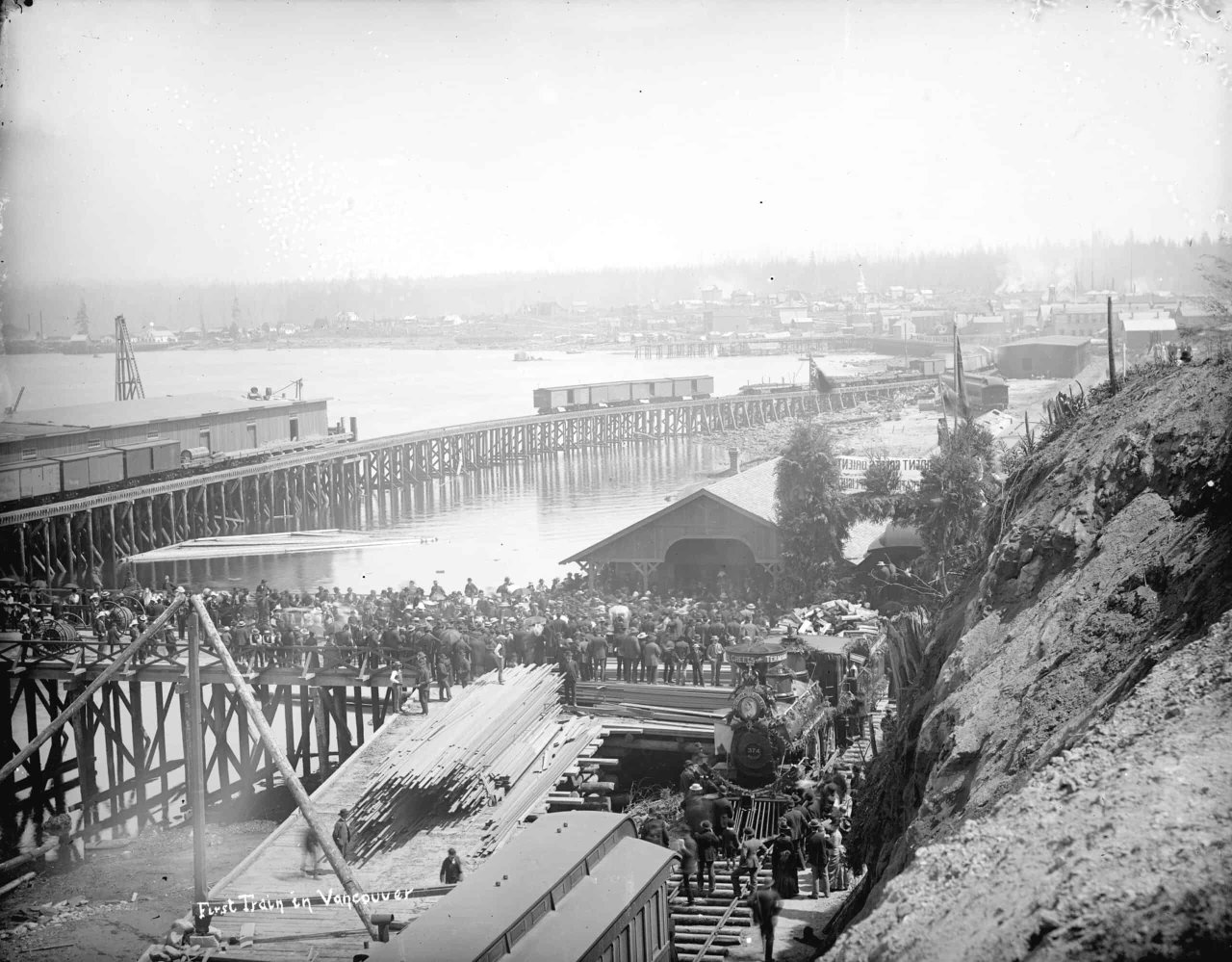

The decision in 1884 to make Granville the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) terminus assured the settler city’s fate, turning a waterside town into a major transportation hub. With massive changes on the way, the City of Vancouver was incorporated in April 1886 and then burned to the ground in June 1886. As almost all of the settler community was within the bounds of Granville Townsite, ‘Gastown’ was obliterated in a matter of hours. The number of early Vancouverites killed in the Great Fire remains uncertain. The elimination of the bucolic village, however, set the stage for rebuilding and renewed growth. None of the buildings in Gastown today are survivors from before the Great Fire. They are, thus, representative of the ambitious period that followed.

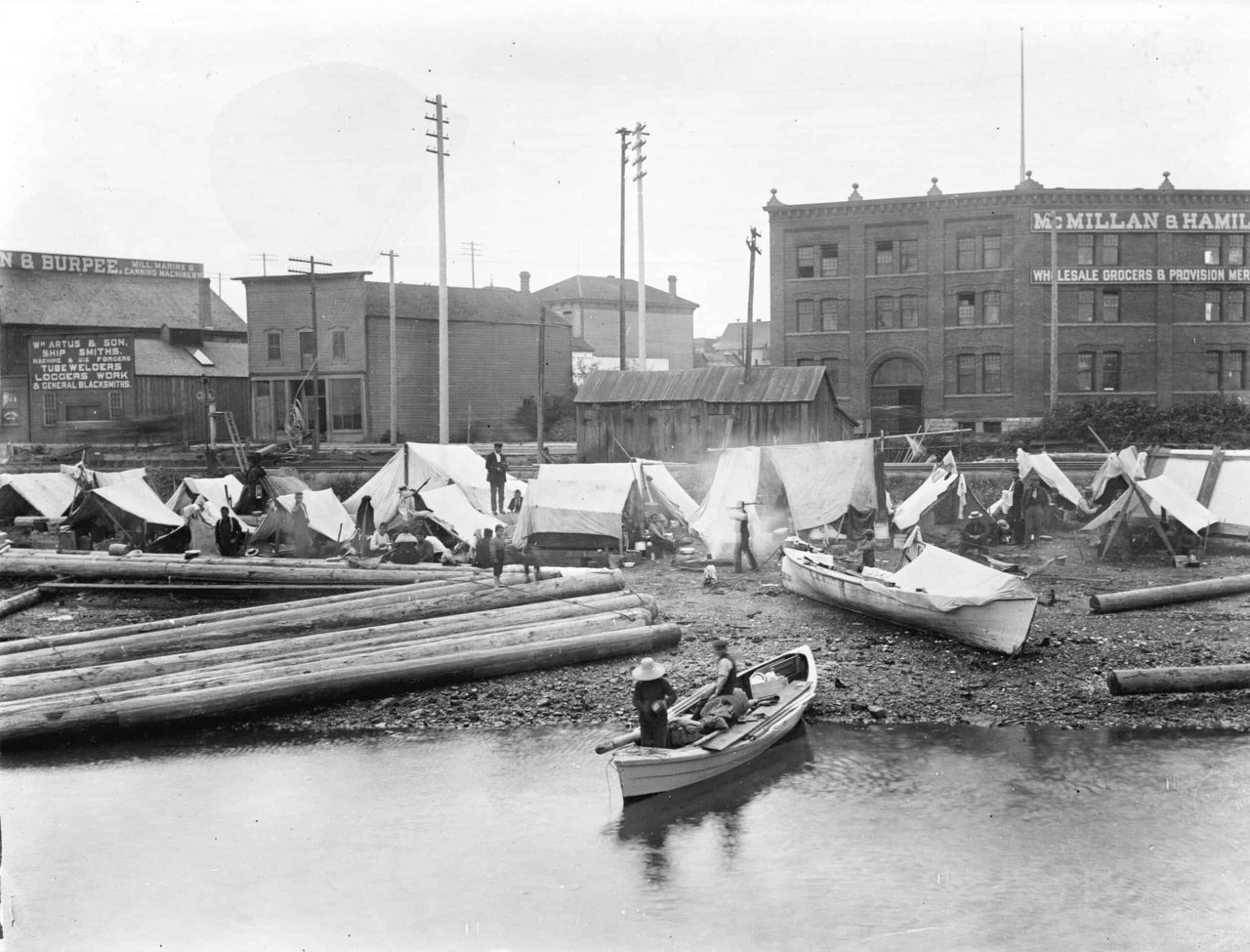

A large working-class population supported the resource and transportation industries that shaped Vancouver’s early years and much of it was concentrated in and around Gastown. The makeup of this population was diverse, including Indigenous peoples as well as settlers and temporary workers from all over the world. The permanent population of Granville also included early Chinese settlers like the Wah Chong family, pictured in an 1884 photo standing outside their laundry business. After the city’s incorporation and the introduction of regular train service from the east and ship traffic from the west, the number of settlers of British origin in Vancouver grew and other populations were pushed to the margins. This period saw the displacement but also the endurance of marginalized populations in the Gastown area. In 1887, the police expelled the occupants of an Indigenous workers’ settlement to the east of Hastings Mill, citing “nuisance”. Despite this, the settlement continued to exist in subsequent years. Images from 1899 show an Indigenous encampment, identified in some records as a salmon fishing camp, on the shores of Burrard Inlet at the foot of Columbia Street in the heart of present-day Gastown. The Chinese community, likewise, was pushed further south to the area between Carrall and Abbott Streets on what is now Pender Street, forming the core of Chinatown.

The area around Gastown remained the city’s commercial core even as the CPR was developing its holdings in Vancouver’s present-day financial district and the West End. Warehouses dominated the old Townsite, along with saloons and bars. By the 1930s it is reckoned there were over 300 establishments serving liquor in Gastown. Hotels remained an important economic feature in the neighbourhood, but churches were conspicuous by their absence (the nearest were further east, closer to Main Street and Strathcona or along Dunsmuir Street to the south). But the die was cast by the CPR: large retail and more exclusive office buildings began to rise along West Hastings Street and up Granville Street, more desirable residential areas were developed in the West End, and Yaletown emerged as a working-class neighbourhood. Businesses, hotels and industry moved out after the First World War and new construction in Gastown stalled for decades. This economic stagnation meant that the historic buildings of Gastown were left behind.

In the post-WWII era the old city centre entered into a period of decline. Vancouverites who could afford to do so in the booming postwar economy moved to suburbs in East and South Vancouver and beyond. Increasingly those who worked in the downtown were commuting in each morning in private automobiles, leading to traffic congestion in the city centre. In the late 1960s, Gastown was one of the neighbourhoods threatened by proposals to ease traffic by means of a waterfront and elevated freeway. Protests and organized community resistance prevented the destruction of Gastown and Chinatown, and most of Strathcona. This threat to Vancouver’s historic neighbourhoods led to renewed interest in their heritage value. In 1968 the Community Arts Council organized walking tours to draw attention to Gastown. A few years later, in 1971, the Province of BC recognized both Gastown and Chinatown as Historic Areas, protecting many of the buildings within their boundaries.

The 1970s saw a great many properties in Gastown restored and repurposed as boutiques, restaurants, music venues and tourist giftshops. These changes had to contend with older continuities: the neighbourhood had been – since its earliest days – the home address of many low-income residents, seasonal workers and squatters. A riot in 1971 drew attention to the presence of a resident community less concerned with heritage preservation than with cheap accommodations. Successive beautification and restoration campaigns have dovetailed with efforts to create a more complete economic zone. The addition of large numbers of condominiums, rental units and social housing along with grocery stores and other necessary day-to-day services transformed the neighbourhood into a hub of activity. While often associated with tourism, shopping and nightlife, Gastown’s boundaries, as defined by the Historic Area, have some overlap with the Downtown Eastside—one of the poorest postal codes in Canada. Depending on who one asks, different blocks may be considered colloquially part of Gastown or the Downtown Eastside. For this reason, Gastown’s mix of long-established businesses and social services with designer stores and high-end restaurants often features in conversations around gentrification and wealth inequality in Vancouver.

Gastown’s protected status has meant that the neighbourhood has maintained a distinctive look. As of 2002, design guidelines are in place that ensure that new development is compatible with the heritage character of the neighbourhood. The harbour and nearby transportation hubs that shaped Gastown’s early years have continued to influence the area’s reality (before the COVID-19 pandemic), with souvenir shops and businesses receiving visitors from the nearby cruise ship terminal.

Heritage Value and Significance

Gastown today is significant for its connection to early Vancouver history. It is an offshoot of the Hastings Mill site further east, growing up around the settler city’s early resource economy and expanding through the development of transport connections. Its subsequent neglect and renewal also tells the story of shifting patterns of urban development.

The majority of the architecture in Gastown dates from between 1886 and 1914, between the renewal spurred by the Great Fire and the beginning of World War I. The heritage significance derives from the distinct style of the neighbourhood, with its masonry construction and varying building height. The street pattern follows the natural curve of the inlet, distinguishing the area from the city around it and resulting in many ‘flat-iron’ buildings.

As a popular tourist destination, Gastown features a mix of old and new. Some of its distinctive features are newer than they look. For instance, one of Vancouver’s most famous landmarks, the Steam Clock, dates back only to 1970. It was part of a significant early 1970s restoration that included the erection of the controversial Gassy Jack statue, the installation of globe street lamps, and the repaving of the streets with brick. Although these additions are not original, they have also been recognized as a feature of the neighbourhood’s heritage character.

Recognition and Regulation

The City of Vancouver and the Province of BC first recognized Gastown as a Historic Area in 1971. The partnership came about because at the time the City could not designate sites independently. Instead, the Province used the Provincial Archaeological and Historic Sites Protection Act of 1960 as the basis for protecting sites within the neighbourhood. In 2009, the Government of Canada recognized the neighbourhood as a National Historic Site. There are 14 buildings from before 1914 within the site.

The Gastown Historic Area is presently referred to as HA-2 in the City’s zoning bylaws. Buildings in this area are subject to additional regulations even if they are not on the Vancouver Heritage Register. Some sites in the area are listed on the Register as protected but have no A, B or C classification. This is because the Province originally protected these sites as part of the creation of the Historic Area and this category of protection remains even as the City’s system of heritage classification has evolved. These designated sites in Gastown are represented on the Heritage Site Finder with an ‘O’.

Explore the Heritage Site Finder’s individual entries on Gastown sites to learn more about the neighbourhood!

Further Exploration

Place Names Map, Musqueam Indian Band, https://www.musqueam.bc.ca/our-story/musqueam-territory/place-names-map/

Squamish Atlas, Kwi Awt Stelmexw, http://squamishatlas.com/

Gastown Historic District, Parks Canada https://www.pc.gc.ca/apps/dfhd/page_nhs_eng.aspx?id=12392

Gastown Historic Area Planning Committee, City of Vancouver, https://vancouver.ca/your-government/gastown-historic-area-planning-committee.aspx

Blood Alley Square Redesign, City of Vancouver, https://vancouver.ca/home-property-development/blood-alley-square-redesign.aspx

Gastown, The Gastown Business Improvement Society, https://gastown.org/

Gallery

Map

Contact

Please Share Your Stories!

Send us your stories, comments or corrections about this site.